O impeachment da presidente Dilma Rousseff pode resultar no fim das investigações da Operação Lava Jato, afirmou na segunda-feira (18/04) o jornal britânico The Guardian, que classificou o processo como “uma tragédia e um escândalo”.

De acordo com o editorial, “agora muitos temem que a campanha anticorrupção desaparecerá, com exceção de uma concentração final de fogo em Lula”.

O jornal afirma que o vice-presidente, Michel Temer, enfrentará os mesmos problemas de Dilma Rousseff, “e suas chances de lidar com eles [problemas] de maneira efetiva devem ser classificadas como baixas”.

“É difícil imaginar um cenário mais sombrio para o Brasil”, acrescenta a publicação.

The Guardian diz que o processo de impeachment, “longe de resolver a polarização política e social do Brasil, exacerbou ambas”.

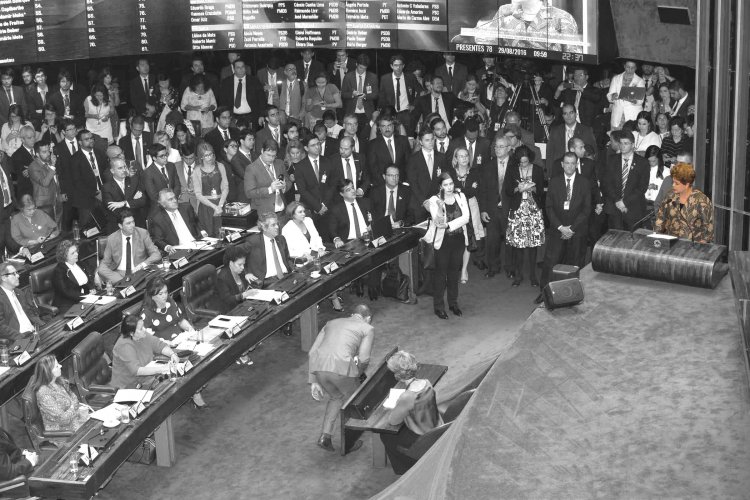

O muro de aço na Esplanada dos Ministérios em Brasília para separar manifestantes a favor e contra o impeachment no domingo (17/04) foi um “símbolo” de até onde a polarização no país chegou, de acordo com o texto.

O editorial considera “paradoxal” o fato de Dilma não estar envolvida nas investigações sobre corrupção na Petrobras que são a base da Operação Lava Jato. Segundo a publicação, as motivações que deram origem ao processo de impeachment da chefe de Estado – as chamadas “pedaladas fiscais” – não seriam mais do que um “delito de menor gravidade” de acordo com padrões brasileiros.

“No entanto, todos aqueles envolvidos em seu impeachment são suspeitos de corrupção, incluindo Eduardo Cunha, o presidente da Câmara”.

Segue o editorial original em inglês:

The Guardian view on Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment: a tragedy and a scandal

Editorial

Nothing is clear in Brazil’s murky political crisis, except that the country will suffer the consequences for a long time to come

Ever since Stefan Zweig, writing in 1941, dubbed it “the land of the future”, Brazil has been reproached for failing to live up to the promise that its size, its resources and its insulation from the wars and troubles afflicting other parts of the world seemed to hold out. There have been moments when that promise seemed on the verge of becoming a reality, but such hopes have again been repeatedly dashed. The most recent came with the accession to power of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2003. Lula and his Workers party, or PT, brought new ideas, new energy and a new style into a Brazilian politics disfigured by corruption, patronage, and persistent procrastination in the face of the pressing issues before the nation.

The PT was a real party, with a mass base across the country, a coherent ideology, an apparently strong moral sense – characteristics that other political formations largely lacked. Lula’s social policies brought him and the PT immense popularity, re-election for a second term, and helped his successor, Dilma Rousseff, to convincing victories in 2010 and 2014. Since then the story has grown darker and darker until it reached a dismal low point on Sunday when the lower house of Congress voted to impeach her. And it could get worse, because the impeachment, far from helping to resolve Brazil’s political and social polarisation, has already exacerbated both.

The steel wall erected along the length of the Esplanada, the parkland strip in the centre of Brasilia, to prevent anti-Dilma and pro-Dilma supporters from physically clashing during the impeachment vote was symbolic of how far such polarisation has already gone. The historian José Murilo de Carvalho said recently thatradicalisation and intolerance in the country have reached a very dangerous point.

How did things go so wrong? The answer is variously to be found in global economic change, the personality of the president, the PT’s embrace of a corrupt system of party finance, the scandal that exploded as that system was exposed, and the dysfunctional relationship of the Brazilian executive and legislature. The economy went into decline as prices for the commodities that are Brazil’s main exports fell sharply. Growth slowed, then halted, then reversed; employment faltered; prices rose and the social provisions that Lula had introduced became harder to finance. The PT itself, once the country’s least corrupt party, chose to solve its financial problems by dipping into a trough of money diverted from Petrobras, the national oil company. Its coalition allies, and other parties, joined in.

Finally, Brazil’s constitution, which pairs a popularly elected president with an open-list PR vote for members of Congress, is a recipe for conflict at the best of times. A theoretically powerful leader is as a result confronted with an array of parties that he or she must woo with jobs, ministries and policy commitments if a coalition supporting the president is to be put together in Congress. The result can be an executive that has lost half its room for manoeuvre before it has even begun to attempt to rule. Lula was a master at managing these contradictions. President Rousseff, ineffective and inconsistent, lacked his skills.

When the public prosecutor and the federal police began investigating the Petrobras affair, and the federal judge Sergio Moro then took it up, did they foresee the damage these revelations would cause? Probably not: the intention seems to have been to purify Brazilian politics, taking as precedent the Italian ‘‘clean hands” investigation of the 1990s.

But the paradoxical outcome is the opposite. The president herself has not been implicated in the Petrobras scandal. The grounds for her impeachment are that she manipulated state funds ahead of the last election – not much more than a misdemeanour by Brazilian standards. But almost all those involved in impeaching her are suspected of corruption, including Eduardo Cunha, the speaker of the lower house.

Now many fear the anti-corruption campaign will fade away, apart from a final concentration of fire on Lula. Michel Temer, the vice-president will face the same problems that defeated Dilma Rousseff, and his chances of dealing with them effectively must be rated as low. A discredited opposition will be taking over from a discredited PT. It is hard to imagine a more gloomy landscape for Brazil.